Bundengan Stories: Folk Zithers and Duck Herders in Wonosobo, Central Java

Location: Ngabean Village, Wonosobo Regency, Central Java

Sound: Bundengan (also called kowangan or koangan)

By the time the Dutch civiil servant and ethnomusicologist Jaap Kunst made his way through the volcano-studded highlands of Central Java on his expeditions of the 1930s, the instrument he called kowangan was already “gradually [becoming] very rare.” Always smitten by rare and exotic instruments, Kunst included multiple photos of the instrument in his massive “Music in Java: Its History, Its Theory, and Its Technique,” understandably as the instrument is so hard to put into words. Kunst describes it as a “shield-like” construction, while I might describe it as having the form of a beetle’s shell (the word kowangan is said to come from the local Javanese word for a kind of beetle). Imagine a woven bamboo mat held vertically, its top two corners folded and tied together. It's the rare kind of object where even after seeing one in person, you could still have no idea what exactly it's for.

An Australian conservator named Rosie Cook e-mailed me last year asking about an instrument called “kowangan” - had I heard of it? She’d come upon a dusty kowangan in the Music Archive collections of Monash University in Melbourne, later learning that the instrument had been collected by the preeminent queen of Indonesian ethnomusicology, Margaret Kartomi. Kartomi had come upon the instrument in the highland area of Dieng in the 1970s, and after some minimal research had shipped an example back home to Australia where it had been collecting dust in the archives ever since.

As a conservator, part of Rosie’s job is diving deep into the material physicality of objects, such as trying to understand the preservation of dried bamboo leaves and the precise weaving of a kowangan’s bamboo lattice. What I didn’t know was that conservation as an art and science is moving away from an obsession with objects as pure material and towards an emphasis on an understanding of objects (from musical instruments to puppets) as being loaded with meaning and cultural significance, a web of cultural context and knowledge which is easy to miss when museum collections are seen as a bunch of old, exotic objects on dusty shelves.

When Rosie told me that she was planning to go to Wonosobo, Central Java to try to find out more about the instrument and this beautiful web of meaning and tradition that surrounds it, I couldn’t help but invite myself along. I had seen the pictures and description in Kunst’s book, but so much was missing. Kunst was pretty old school, a classic colonial surveyor, and as such he was usually more interested in making lists of instruments and tuning systems than in finding out what the music meant to people, or why it was played at all. This instrument, we thought, deserves more.

A few months later, we were in Wonosobo, a cool highland area a few hours from Java's cultural capitals of Solo and Jogja. One of our first stops was at the humble workshop of Pak Mahrumi, the last craftsman of kowangan in the area. The kowangan, it turns out, is not the name for a musical instrument at all, but rather for the duck herder's tool from which the instrument arose.

What locals still call kowangan is up to this day the favored tool of the duck herder (penggembala bebek in Indonesian - yes, there is such a thing), men who shepherd their herd of ducks out to the fields to graze. As they wait on their fowl friends, these penggembala prop up their kowangan with a piece of wood or rattan and sit underneath it, the organic curves of the kowangan shielding them from sun and rain. When it's time to go, the herder can hang the device off the back of his head like a rigid cape.

At some point, some bored duck herder decided that the three-in-one hat, cape, and shelter combo simply wasn’t enough - there was musical potential here! The kowangan was already wrapped up in ijuk, or “palm hair”, a kind of natural fiber which when unraveled makes a perfect string. These strings were strung across the concave interior of the kowangan, probably in imitation of the Javanese folk zither called siter. This bored duck herder, not satisfied with making a simple zither, took it a step further: he wedged bamboo strips into the lattice of the kowangan, their tops poking out like fingers. When plucked, these strips became kendhang, or drums, the dry bassy sound approximating the busy polyrhythms of the Javanese kendhang drum.

Pak Mahrumi, the kowangan craftsman (seen above), has nothing to do with this music making. He just makes kowangan, the duck herder’s shelter - what the duck guys do after they buy it is up to them. Once transformed by the duck herder/musician into a working instrument, the object is actually no longer called a kowangan. It has been transformed through that beautiful musical alchemy into something totally new: the bundengan.

Despite knowing little about the musical experimentation of duck bros and modern revivalists, Pak Mahrumi was a well of knowledge about the kowangan at the heart of the musical bundengan. We spent an hour or so in his little studio as he began the work on a new kowangan, confidently weaving horizontal bamboo strips (penyendek) with vertical ones (pendawa), eventually forming such a firm lattice that he had to use a hammer to whack the strips into place. Later the corners of this fence-like mat would be folded up and tied with the aforementioned ijuk into a peak-like horn or sungu, which doubles as a handle. The lattice would then be covered with sompring, the bark-like sheath of young bamboo, “on top of one-another”, Kunst put it, “like the scales of a fish.”

To get to the heart of what happens after a kowangan has become a bundengan, we had to meet with Pak Munir, the man who some say is the last real master of bundengan in all of Java. This is quite a contentious subject, it turns out. Before heading to Wonosobo, Rosie and I had both seen a documentary (and an article or two) which described a guy named Hengky as the last bundengan pro. They couldn’t both be the last bundengan master…what was going on?

Pak Munir, it turns out, has something of a genetic claim to the bundengan throne. His older brother was a man named Pak Barnawi, a musician who locals credit with taking the private duck herder’s music and turning it into a modern performance art. Pak Barnawi had taken the twangy palm fiber ijuk strings and swapped them out for the synthetic strings of a tennis racquet, and he’d been the first to play the instrument on a stage rather than in a field full of ducks. Barnawi had died in 2012, and Pak Munir, his kid brother, had been cajoled by a local music patron into taking his place as gatekeeper of the bundengan tradition.

It became clear that claiming to be the only bundengan musician left in Wonosobo is a pretty crafty move, as if you’re the only guy left, you’re bound to be the one called when local government wants to put on a concert showcasing “regional arts,” or when the local TV crew comes through looking to spotlight this oddball musical tradition. That’s why this younger fellow, Mas Hengky, had claimed to be the last guy as well (Pak Munir shrugged Hengky off, essentially saying “yeah, he can play, but I’m the only one left who can really play”) And it wasn’t just a rivalry between Munir and Hengky - on our two day sweep through Wonosobo looking for surviving bundengan musicians, we met two others, Pak Suparman and Pak Muntamar (the latter an actual duck herder, the only musical duck herder we managed to meet) who also claimed to be the only bundengan musicians they knew of. Even stranger, the last two both claimed they’d never met another bundengan player, even in decades past. When asked how they’d learned to play, or how they knew to transform the kowangan into a bundengan, they simply said they’d made it up themselves!

We never got to meet Munir’s rival Hengky, but that was fine enough - Munir was such a treasure. A shy, soft-spoken man with a thick black moustache and intense eyes, Pak Munir didn’t seem well-suited to the role of Bundengan Spokesman into which he’d been forced. Behind the shyness, though, was an inherited wealth of knowledge about bundengan, its theory and technique. If we’d gone to Pak Mahrumi to get into the material of the thing, Pak Munir was a window into the intangible, the musician’s understanding of an instrument.

I sat with Pak Munir before his bundengan and he broke it down for me. We started with those percussively plucked bamboo strips called kendhang or tabuh (in musicology, this part of the instrument is called a lamellophone, a category which includes everything from African kalimbas to mouth harps - the bundengan is the only non-mouth harp lamellophone I know of in Indonesia, a fact which might only be interesting to musical instrument nerds like me.) The kendhang, Pak Munir explained, is the hardest part of bundengan to master - the two or three strips are plucked with the index, middle, and ring finger in the dynamic, triplet-based idiom borrowed from kendhang playing found in local gamelan ensembles. In fact, the whole instrument is meant to replicate the sound of a pared down gamelan, with the four strings (Kunst’s example had seven, but we’re not sure how that would’ve worked) representing the gamelan instruments kenong, bende, kempul, and gong.

The tuning of these four strings can be described most kindly as “idiosyncratic.” Kunst wrote that “the tuning is said to be in slendro [a common pentatonic gamelan tuning]; in reality, however, it resembled slendro only remotely, whilst considerable discrepancies could be heard between the different tudungs [bundengan] playing together.” Sit down with a bundengan for long enough and these “discrepancies” become understandable: the strings are not tuned with any kind of firm system like pegs; rather, they are stretched across and wedged or tied to the bamboo lattice. This isn’t very exacting, or permanent, and that doesn’t seem to be a problem for the musicians.

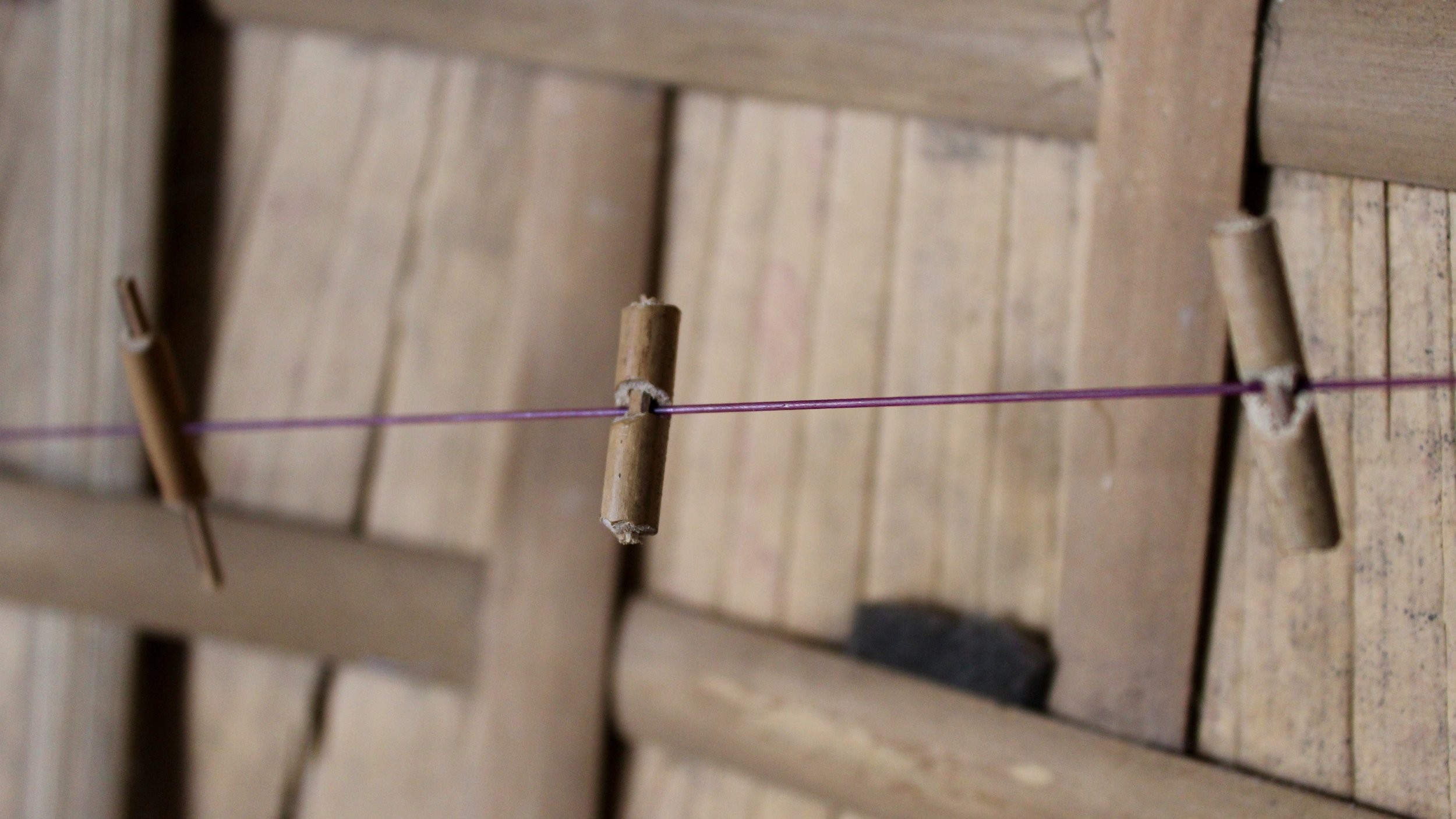

This slippery tuning only began to make sense to me when my friend Agus explained that bundengan musicians tune their instruments not to a particular pitch, but to a particular timbre. So, for example, the gong string doesn’t have to have any special pitch in relation to the others - it simply has to have a deep, rich “gong” sound. The kenong simply has to have a round “nong” sound, the kempul a high and dry "ning", sound, and so on. This is accomplished by using little bamboo pieces (Kunst called them bandulan, but Munir had no name for them) spaced out along the strings. The physics of this is complicated, but these little floating “markers” both weigh the string down, which lowers the pitch, while also complicating the harmonics in such a way that the string has this kind of wavering gong-like sound. Again, we’re getting into dangerously nerdy organology here, but I’ve never seen another string instrument in the world that has anything like this (the closest, maybe, is John Cage’s prepared piano strings!)

For such a large, strange-looking instrument, the music played on it is actually quite simple: literally the same four note pattern is played on every song (for songs in the pop fusion style campursari, the picking becomes more fevered, but that’s the only difference). The “zither” part, then, is not playing a melody like other zithers in Java like siter and kacapi. Instead, it is just holding down the basic colotomic elements (the kind of foundational structure of all gamelan music), with the melody supplied by a singer. In our recording session, as is usual when Pak Munir performs, the bundengan is accompanied by family friend Pak Buhori on vocals (we recorded and filmed the material for this post in Pak Buhori’s living room, right after a dance rehearsal with Buhori’s daughters.) My favorite, though, was the tune where Pak Munir shyly sang himself, just as the duck herders once did.

The songs are taken from different Javanese folk music repertoires, from lagu dolanan (children’s songs) to campursari. Especially popular in Wonosobo is adding a dose of lengger, a dance, theater, and music form popular in highland Central Java. These days performative bundengan is almost always accompanied by lengger dancers and theater, which has its own fascinating history that I just don’t have the space to get into!

Despite seeming to get some kind of prestige from its sheer rarity, the bundengan looks to be entering a new era of revitalization. Rosie and I have been lucky to meet with a new generation of Wonosobo-ites eager to embrace and reimagine the place of bundengan in their society. While bundengan may have become less common over the past century as local culture shifted away from a purely Javanese, agricultural way of life towards a modernizing, globalized culture, it is that rustic, hyper-regional charm which seems to be spurring the bundengan revival now. Young guys like new friends Agus and Yudi are inspired by the bundengan’s unique, romantic past, but they aren’t stuck there - they envision the bundengan as a potent symbol of Wonosobo’s folksy charm, mixing it with indie pop songs and other very “untraditional” experimentations.

Meanwhile, a local teacher named Bu Mul is leading a bundengan revolution with her young students, commissioning literally hundreds of new kowangan/bundengan from Pak Mahrumi for her students to play, even coming up with tiny versions that are easier for her kids’ tiny fingers to get a a hold of. Just this month, Rosie even returned to Wonosobo to take part in a bundengan workshop with Bu Mul and dozens of schoolkids.

This is a whole new world of bundengan. When Kunst found (what he called) kowangan in nearby Boyolali, he poetically wrote how the instruments would be “placed in threes or fours in a close circle with the openings turned towards each other, as a small house or shelter." In this formation, "In complete serenity and peace of mind, squatting, dry and cosy, underneath this contraption, and with music and song, they wait until the shower is over.” I love this image, I really do, but that world is gone now. Bundengan is finding its way forward in a new context, with a new generation giving it new meaning. There’s even a hashtag, #bundengan, where bundengan enthusiasts can share their latest discoveries and creations. It may not have the naive charm of duck herds in a field, but its just as real, and just as alive.

+++

Huge thanks, in no special order, to Rosie, our friendly assistants Aji and Budi, Pak Buhori and family for hosting us, Pak Munir for the ilmu, plus Pak Suparman, Mahrumi, and Muntamar. Also to the new bundengan generation, Agus, Yudi, Sa'id, and Bu Mul. And can't forget local documentarians Pak Agus and Pak Bambang Hengky. What a crowd!

Follow #bundengan and check out Rosie's Instagram, @rosiehcook, where she promises to soon release her amazingly comprehensive thesis on bundengan!