Papuan Strings, Pt. 1: Songgeri

Location: Kawipi, Kepulauan Ambai, Yapen Regency, Papua

Sound: Songgeri

It’s Sunday, and I’m in a church in Kawipi, a small village in the Ambai archipelago of Papua. As the service starts, the vaulted ceilings of the church come alive with music.

This fact is not remarkable in itself: after a century and a half of fervent land-grabbing by Christian missionaries, this massive region in the east of Indonesia is one of the most firmly Christian parts of the country, and music has long played a central role in churches across the area (see this remarkable droney Dani singing in a Catholic church in Yahokimo recorded by my friend Markus Rumbino, or some spiritual yospan played by a church group in a prison in Abepura!)

What strikes me, though, is just how familiar and unfamiliar the scene in this particular church feels.

Familiar: Folks are stomping their feet, clapping their hands, singing their hearts out in rapturous harmony. I’m not a regular churchgoer, but as an American who’s watched a lot of movies and gone through a Sacred Steel phase, I feel like know it regardless: this is gospel, or some version of it anyway.

Unfamiliar: Four giant mutant double basses are shaking against the pews as men sit facing the strings, plucking them with wild enthusiasm with both hands. At least ten ukulele lutes are getting scratched with equal fervor, strings breaking every few minutes. Voices soar in Ambai, a somewhat rare Austronesian language in a Melanesian world.

Indeed, there is a lot of church music happening across Papua, but none quite like this. This is songgeri.

The wonderfully shaped island of Ambai sits just south of the large island of Yapen (often known to outsiders as Serui after its largest town, just visible here in the top-left) in Papua’s Cenderawasih Bay. [photo from Google Earth]

There are two ways of explaining how this musical world came to be. When I asked the musicians of Kawipi about the history of their music, their answer began: “In 1956, the Pentecostal torch brought the true light of the gospel to our village.”

For the deeply religious folks of Kawipi, the history of songgeri in their village is the history of the Pentecostal church. The elders walk me through a line of succession: In that year, the pastor Jonathan Itaar brought the teachings of Pentecostalism to the islands from Manado in North Sulawesi. From Jonathan Itaar, the role of spiritual shepherd (gembala, as Indonesian Pentecostalists call their leaders) was passed to Permenas Yowei, then to Simon Sikowai, next to Jordan Oroba, and finally, when he passed, to his wife Esterlina Oroba. This line of gembala was repeatedly stressed to me as central to understanding songgeri: in a community built around a single church, the spiritual space that they fostered made songgeri what it is today.

As a strain of Christianity that stresses individual, ecstatic communion with god, the Pentecostal church often embraces a particularly expressive and musical mode of worship. In the beginning, a pastor explained, the Ambai people did not yet know musical instruments other than the tifa drum. In early services, folks would simply clap their hands and sing, often mixing in anuai, a form of spontaneous oral poetry common across the Ambai and Yapen islands (similar vocal traditions can be found across the larger Cenderawasih Bay area - see the well-recorded wor of nearby Biak, or the amunai of Waropen across the strait.) Sometime around the late 60’s to 70’s, though, in came the strings.

This is where it might be helpful to zoom out a bit, as folks in Kawipi couldn’t speak much to the wider history of songgeri across the islands around Yapen, or even to the existence of so-called string bands in general. With that being said, much of musical history in this part of the world is hazy, and how exactly string bands came to be so popular across the eastern part of Indonesia is largely up for speculation (see some earlier wild guesses in my post on the yanger string band tradition of Halmahera.)

One way of understanding this musical format and its history is to escape my nationalistic lens for a bit.* It’s important to remember that we’re in Papua (administratively and culturally, if not on the “mainland”!), an area very much in the Melanesian cultural sphere of the Pacific. This is a place where, in discussing music with local friends, I heard more mention of Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, and the Solomon Islands than those Austronesian islands to the west that I’ve more often explored.

Ethnomusicologist Michael Webb has written extensively on the history of string bands (or stringbands as it’s often written) in Papua New Guinea, and while much of his writing focuses on the independent half of the great island of New Guinea (PNG), so much of it seems to apply to this side of the border. In Melanesian Worlds of Music and Dance, Webb writes how missionaries’ introduction of Christian hymnody in PNG laid a foundation of singing and music-making in a Western, largely diatonic idiom - likely true in Ambai as well, where the Protestant mission had introduced Christian song in the early 20th century even before the “Pentecostal torch” made its way there.

Later, in the 1930’s and 40’s, Webb writes, “Hawaiian guitars, ukuleles and songs were circulating far and wide, including along Pacific shipping lanes.” This is certainly the case in Indonesia as well, though this simple history of dispersal is complicated, as I wrote on yanger, by a much longer history of Portuguese influence, at least from Java into the Spice islands - see the widespread influence of syncretic keroncong music from Jakarta to Sulawesi (even the tiny ukulele-like instruments played in Asmat string bands on Papua’s south coast are called kroncong.)

Finally, Webb writes, there’s a period in the mid-20th century where guitars quickly become more widespread as Western musical styles like swing and early rock idioms like boogie woogie, were being absorbed through wartime entertainment (Americans often don’t realize that the whole of New Guinea was central to the so-called Pacific Theater of War during WWII - especially on Biak, another string band hotspot I’ll explore in a later post.) How exactly this transmission happened in Melanesia is still somewhat opaque, but it’s undeniable - some of the bass lines in Biak string bands and, more rarely, songgeri, are straight out of early rock and country. Webb also writes how the tea-chest bass of Vanuatu string bands was a borrowing from skiffle, a cultural diffusion that somehow eventually made its way all the way to Maluku (in those wonderful yanger groups) and even as far as Sangihe in North Sulawesi (where I recorded a similar bass in an orkes string band back in 2018.)

It is from this wider scene of musical diffusion and exchange that songgeri likely emerged, along with the Pentacostal torch, in the mid-20th century. It’s easy to see, now, how songgeri exists in a wider landscape of Melanesian (and Indonesian!) string bands, but songgeri is not just any string band tradition. I’ve heard a lot of Papuan string band music (at least on YouTube!), and there’s a certain uniformity to it - lots of waltz rhythms, lots of melodic guitar picking, and lots of self aware anthems (most of this uniformity is likely thanks to the influence of one man, but that’s a topic for the next post!) However, songgeri breaks the mold in a lot of delightful ways that are worth exploring.

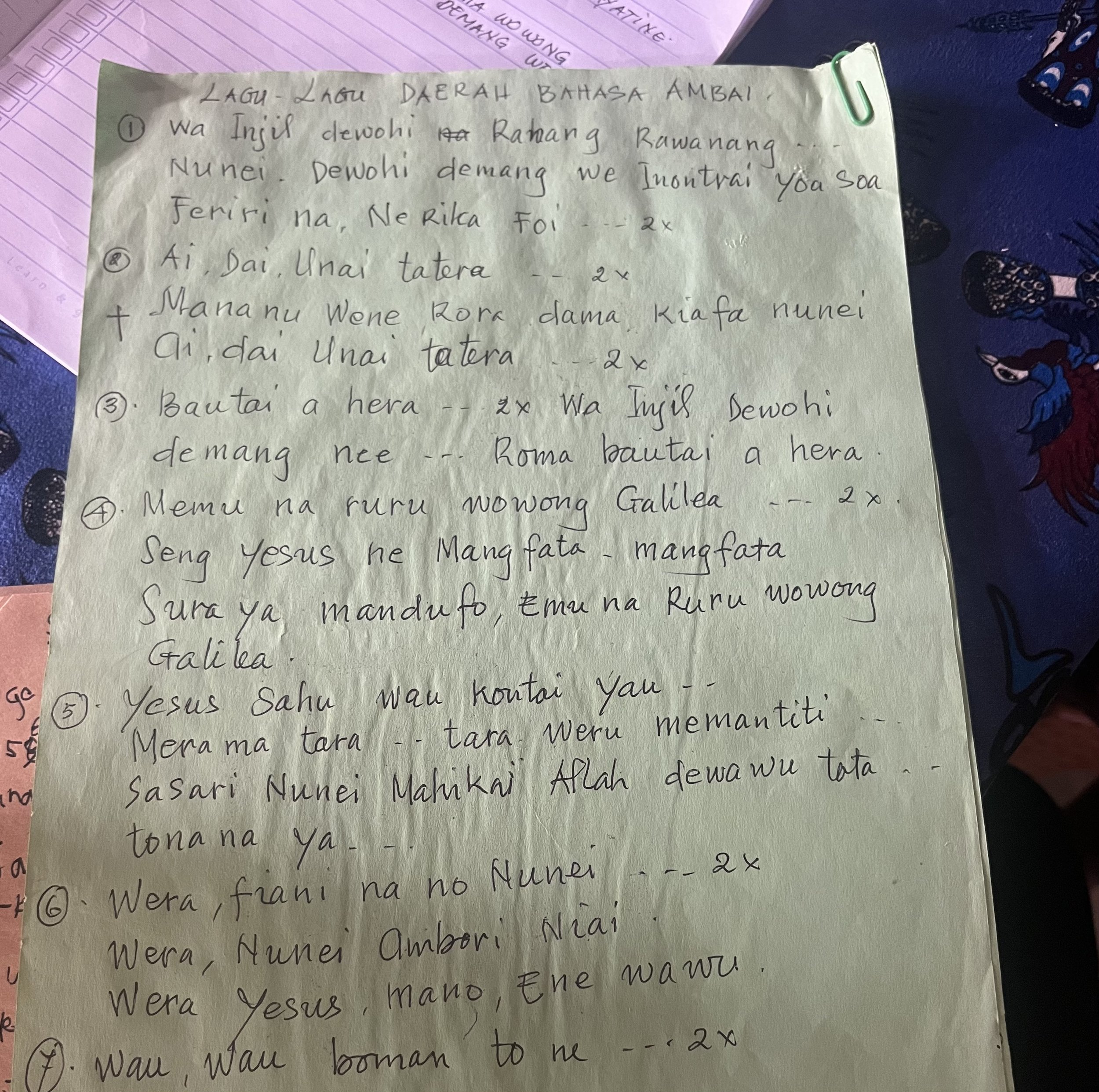

Webb has another great article on Pentecostal church music in PNG that has helped me think about what makes songgeri so special in form, content, and performance. In it, Webb cites “Global hymnologist Michael Hawn” (what a title!) in describing two types of religious hymns, sequential and cyclical. Sequential hymns have a progression, developing themes over a number of stanzas. Meanwhile, Pentecostal (and especially indigenized) hymns tend towards the cyclical, with short refrains looped as long as necessary. This is definitely the case with songgeri, where musicians create epic medleys that are actually made up of short stanzas repeated as long as the group is vibing on the message and melody. The following are a few examples - the title of each piece is simply the first line (take note of the maritime themes, and how the Sea of Galilee draws parallels with the familiar waters of Cenderawasih Bay!)

Emuna ruru wowong Galilea

Seng Yesus ne mangfata-mangfata

Sura ya mandufo Emuna ruru wowong Galilea

Emuna ruru wowong Galilea

Casting nets in the Sea of Galilee

The Lord Jesus and his disciples

Twelve disciples

Casting nets in the Sea of Galilee

Casting nets in the Sea of Galilee

+++

Naromu warapemang

Jau isifo, jau isifo

Jau isifo, jau isifo to sorga

On the wings of an eagle

I soar, I soar

I soar, I soar to heaven

+++

Nemunu doana kamia wowong

Rautu rora tifai

Demang we tata

Nemunu doana kamia wowong

His house is built on coral

The gates of heaven are open

He awaits us

His house is built on coral

+++

These short, cyclical stanzas remind me of Ambai oral traditions such as the previously mentioned anuai or singing for the mandohi dance, in which a singer will call out a short verse until the verse is joined and repeated by the larger group. This, too, is how songgeri flows: the short stanzas are repeated by all in a joyous loop until somebody jumps in and sings a new line, after which the rest follow suit.

Digging deeper into the history and theology of Pentecostalism and its music, I truly began to see how so much of what sets songgeri apart from other string band music in Papua is rooted in the particularities of the faith and its practice. Pentecostals put a premium on a personal, ecstatic spiritual experience, and since the birth of Pentecostalism on Azusa Street in early 20th century Los Angeles, music has been an essential element of that experience. Putting a premium on spontaneity and orality, music-making allows the Pentecostal worshipper to “bathe in the holy spirit” in a particularly embodied way, with collective hand-clapping and spirited, full-throated singing the norm.

The “spirit” of songgeri, whether you interpret it as human or divine, is central to so many elements of its practice. On the one hand, there’s the name itself: songgeri in the Ambai language means “joy” or “ecstasy” (my interpretation of the Indonesian translation, suka cita.)* This channeling of a spiritual ecstasy through music is seen in every facet of the songgeri tradition, from those short, looping verses that encourage collective participation and spontaneity, to the musical structure itself - nearly every songgeri song uses exactly the same three chords, young songgeri musician Juna explained, “so everyone can follow along and we can focus on the spirit.”

This pared down path to spiritual ecstasy can even be seen in the instrumentation itself: the various songgeri lutes (from the four-string variety, called ukulele despite their size and shape, and the five-string gitar) are all tuned specifically to allow for simple fretting of those three essential songgeri chords. Songgeri instrument makers don’t even bother adding more than the top one or two frets on these ukulele, knowing full well that the music will only ever call for that streamlined handful of chords!

Speaking of simplified, ecstatic strings, consider the thunderous foundation of the ensemble’s stembas, a kind of reimagined double bass. Unlike in other Papuan string bands where the bass is either laid down (see also the bas tidur in some old school yanger ensembles of Halmahera) or played more or less “conventionally”, the stembas of songgeri are played with the instruments flipped around, with the strings facing a seated musician. Two thick nylon strings (“fishing line to catch sharks,” the musicians explained) are tuned a fourth apart and plucked with a specially made wooden pick (gati-gati, made from kayu ropi or kayu aninu wood) for maximum volume. Again, everything from the ergonomic playing to the tuning and even the wooden pick have all evolved from the imperative to be simple and loud, the better to accommodate the spirited, communal music-making that is at the heart of songgeri.

Born as worship music, songgeri is most at home in the frequent services, ibadah, held in Pentecostal churches in Ambai and around nearby Yapen, as well as the churches of diasporic communities of orang Serui** in cities of the Papuan “mainland” like Manokwari and Jayapura. Playing from a set of pews set in front of the congregation, a songgeri band can be twenty strong: the Kawipi band featured three stembas and more than a dozen folks on ukulele and gitar. This is communal music-making after all, so as the band plays, the whole congregation joins in, dozens of people singing, clapping, and stamping their feet.

Outside the feverish atmosphere of the church service proper, songgeri takes a more relaxed form. On multiple occasions during my stay in Kawipi, musicians would linger after a sweaty service, or even just hanging on their front porch above the water, and play. These were more mid-tempo jams, often with one singer predominating and choosing the next verse. As the tempo slowed, I could hear a particularly Ambai sense of melody and timing show itself a bit more boldly - vocalists bent the tunes with blue notes, Ambai language lyrics predominated, and even something of a mournful character seemed to emerge.

It’s always a good sign when, even after I’ve turned off my digital recorder and packed up the mic stand and cables, the music plays on. It shows me the music isn’t a chore, an old relic played just for the foreign guest then tucked away for the next few years until another documentary crew comes by. The Kawipi songgeri crew’s nearly non-stop music-making, be it joyful or mournful, was a sign of something I’ve always implicitly understood but never put into words: musical traditions thrive when that music is both deeply meaningful and also, simply, brings joy, either for the musicians or for an audience. Songgeri is tied to a faith that loads it with meaning and joy, and so it thrives. It will certainly change, as all traditions do, but I have my own kind of faith: songgeri will keep on strumming.

Context:

I’ve been considering doing away with this section, with my blog-like rambling at risk of centering my own story when that’s really the opposite of my intentions with Aural Archipelago. But sometimes, the story of how a recording came to be is so delightful, so unbelievable, that I simply have to tell it.

I found songgeri on YouTube years ago and immediately became obsessed: even before I knew that songgeri meant “joy,” I was already thinking that this must be some of the most joyful, heartfelt music I’ve ever heard. By watching dozens of videos, I eventually got the idea of where this music was being played - Ambai, nearby Yapen, even in the churches of far-off Jayapura - but otherwise had no idea how to make connections with folks there (my typical technique of leaving comments on YouTube videos somehow didn’t pan out.)

Still, I was determined. This past July, I touched down for the first time in Papua, a moment I’ve been dreaming of for more than a decade. Settling into the regional capital of Jayapura, I started to hatch a plan: I’d just go to one of the Jayapura Pentecostal churches I’d seen on YouTube and ask around. My local friend was skeptical: Papua isn’t like the rest of Indonesia, he told me. You can’t just show up to a place without a connection, he said - folks aren’t immediately trusting of strangers in the same way they might be back in Java.

Still without an Ambai contact, I decided to take a motorbike taxi from the suburbs and head to GBI Patmos, a Pentecostal church off the main strip in the center of Jayapura, right off the sparkling blue waters of Humboldt Bay. It was a Tuesday afternoon, so I wasn’t sure if anybody would even be around, but sure enough as I walked into the front yard of the church, I was beckoned in by a bunch of folks sitting around a picnic table eating boiled plantains.

“Do you play songgeri here?” I asked, my voice betraying more timidity than usual as I remembered my friend’s warning. They looked up from their plantains.

“Songgeri? Of course we play songgeri! Sit down, sit down!”

Well, I thought smugly to myself, that wasn’t so hard!

I’d met exactly the right people: sitting to my right was an old distinguished lady, the Mama Gembala - the spiritual shepherdess of this particular flock. Years ago, she told me half a dozen times while I was there, another American, perhaps a missionary, had stayed at the church, and she’d become fond of our type. A young guy at the table, Juna, reassured me: you’ve come to the right place - nearly the whole congregation was orang Serui, migrants from the islands of Ambai and Yapen nearly 500 kilometers away. Almost as proof, Juna brought out their homemade ukulele and stembas, and soon enough I had an invitation to join their next service the following Thursday. Yes, there would be songgeri!

The next Thursday I took another motorbike taxi into town and straight to church. Mama Gembala and Juna ushered me into the rather plain building and past rows of mostly empty chairs to the front row, where I could sit with the assembling songgeri team. Because it was a smaller service, the group was also pared down: just three ukulele, one stembas, and a standard acoustic guitar. I was soon introduced to Pak Otniel, the leader of the songgeri group. Middle aged and with a serious air about him, he had studied anthropology back in university, later becoming a priest. He was intrigued by my intent to research songgeri, and offered to help as best he could.

That service was delightful: somewhat sparsely attended, it was still full of joy. Though I’ve rarely attended church in my life, I was struck by how familiar the scene was, from the vigorous hand-clapping to the “Can I get an amen??” It was a short service - a mini-sermon (I was invited up to give a speech, the first of a few I’d give on that trip!) and a handful of songs, and as soon as I knew it we were wrapping up, eating donuts and drinking tea at the picnic table set up out front.

It’d been great, but I was now, more than ever, eager to go hear songgeri at the source. As we shared a donut, I told Pak Otniel of my plan: I wanted to go to Serui, to Ambai even, to get the full story. “I’ve got you covered,” he assured me. “Just go to my village, Kawipi, and you’ll be taken care of.”

I had no idea just how true that was.

The next week I was in Serui, the port town and only proper “city” on Yapen, a surprisingly large island that stretches across the waters of Papua’s Cenderawasih Bay. It had been a pretty epic journey getting there: a flight from Jayapura to Biak (the better-known island of the bay) followed by an all-day “fast boat” (kapal cepat) that had meandered from Biak, around the length of Yapen to Waropen on the “mainland” before finally anchoring on Yapen’s southern coast. The island of Ambai was just across a narrow strait, accessible only by an even smaller motorboat, so I spent the night in the sleepy port town with a friendly Waropen local I’d met on the boat (thanks Edo!) and arranged to meet my Kawipi contact the next day.

The next morning, I headed to the coast and was met on the beach by Pak Isak, the kepala kampung (village head) of Kawipi and son of the current gembala gereja. Pak Isak grabbed my overloaded backpack (mic stands sticking out the top, a sock or two threatening to spill out) and took my hand as I waded into the water to board a motorboat that had pulled up right onto the shore. His family was already on board, filming the whole thing - already I was getting the sense that this was not an everyday experience for any of us.

Engine running full bore, we were soon skipping across the beautiful blue waters south of Yapen, angling our way around largely uninhabited Saweru and around the northern tip and many azure bays of Ambai’s eastern side. As we swept along Ambai’s coast, the boat began to slow and I began to get the sense that we were drawing closer. A couple hundred meters off the shoreline, the engine was cut and I watched with curiosity as another boat from closer to shore approached us. Festooned in dried palm fronds, it looked almost like a parade float - was this what fishing boats look like here? As it drew up closer to us, I started to hear voices. Someone was singing. Was that the sound of…strings?

The boat drew up closer, right up to ours, and I could soon see through the palm fronds: an entire songgeri band was standing in the middle of the tiny boat, ukulele, stembas and all, singing their heart out. I shook my head in disbelief, a ridiculous grin spreading across my face. They’d arranged a welcoming party, Ambai style. Just for me.

Towards the bow of the welcoming boat they’d arranged a plastic deck chair as if it were a throne, and Pak Isak was soon motioning for me to board. As the boats had lined up side to side, I gingerly stepped from one to another and took my seat in the chair, watching as Pak Isak and all my belongings motored away. The band continued to play without missing a beat as the engine revved to life again and we set off towards a small harbor.

Soon a whole village came into view, house upon house built up on stilts above bright blue water, all connected by rough wooden gangways. Folks waved at us from their porches above the water as we made our way to a pier that jutted out into the bay, itself decked out in palm fronds. There, too, there was music - did they have a recording of another songgeri group playing?

As we drew closer to the pier, my shock grew to utter disbelief: gathered on the pier there was another string band along with dozens and dozens of people, the whole village maybe. As they sang and cheered, my utter shock mingled with a distinct shame: Is this all for me? Do they realize I’m just some guy??

I am, indeed, just some guy, but I am also, it turns out, the one and only foreigner to ever visit their village - a fact made less surprising by the fact that the only way to reach the village is by specially chartered motorboat*** That partly explained the sincere excitement with which I was greeted, but I began to suspect there was more to it. My suspicions were confirmed as I heard a megaphone squeal on and a welcome ring out: “We kindly welcome to Kawipi our honored guest, Mr. Missionary, from…Greece. Mr. Missionary, from Greece, please disembark!”

(Later, I’d learn, Pak Isak had gotten word from Pak Otniel: there was a foreigner who wanted to visit Kawipi and sit in for a church service and learn about songgeri. He’d arranged for a welcoming party, but only half the village had actually gotten the message that I was there to study songgeri - the rest just assumed that the arrival of a foreigner together with the priest and village head could only mean one thing: I was a missionary! The Greek bit will, I have to say, forever remain a mystery. )

Still in shock, I climbed a wooden ladder from the boat to the pier and was greeted by the entire congregation and the second songgeri band. A traditional crown of feathers, beads, and shells was placed on my head and I was made to ceremonially step on two porcelain plates, a ritual called injak piring usually reserved for Ambai folks returning to the village after a long time at sea. Pak Isak reappeared and ushered me onwards towards a church building that dominated the village landscape. As we walked down the pier, I pulled him aside. “Pak, you know I’m not a missionary right? I’m afraid there’s been a misunderstanding.” “I know, I know. It’s no problem. Let’s go.”

At least the musicians had gotten the right intel, as they’d arranged a tableau in front of the church: wooden planks, a saw, a hammer, nylon strings and a half-made ukulele all laid out on some gravel on the narrow spit of reclaimed land between the church and the sea. The generosity of spirit was dumbfounding: they’d been told I was interested in the instrumentation, so an entire demonstration had been arranged to show me exactly how their instruments were made.

Even once I’d settled in and had a seat in front of the church, the music still hadn’t stopped: both bands had merged and were playing on the terrace overlooking the village. Hoping to seize the moment, I immediately took out my gear and recorded one of the liveliest sessions I’ve ever had the pleasure of experiencing: dozens of folks gathered, men and women, young and old, all strumming and singing their hearts out.

After a medley that easily stretched over half an hour, I whispered to Pak Isak: by all means, feel free to stop if you want, that was wonderful - I’ve recorded quite a lot! Surely folks need to go about their day. But despite my polite insistence, it soon became clear that while I was the main impetus for the gathering, the songgeri train had already gathered steam and was out of the station - there was no stopping it.

I stayed in Kawipi for three days, and people almost never stopped playing songgeri. I would wake up, and hear folks singing from their porch, voices cast loud and clear across the water. The morning after I arrived was Sunday, and the Sunday morning service was just as you’d expect: a packed house, the whole village and then some all out in their Sunday finest to sing along with the songgeri mega-group I described earlier. That night? Another service, another songgeri session. After the service? Dinner, then more songgeri.

Before the Sunday night service, I’d taken out my beloved kalimba and shared some of my own sounds, humble as they are, and I’d asked: do you mind if I join along this time? The band was delighted, so I hooked up with a contact mic I brought along and got into the irresistible three chord groove. Between songs, I was asked once more to give, if not a sermon, some kind of speech, some thoughts on what I’d seen and heard so far. Shyly taking up the microphone, I shared my earnest thoughts, perhaps cheesy though sincere: I’d never had an experience quite like this one before, and it was a true and profound honor. Songgeri, I said, is such a pure example of everything that is good about music. It brings us together, America and Ambai. It brings you together, neighbor with neighbor. And, even more profoundly, it connects us mortals with something profound, something deeper and bigger than ourselves. Maybe it’s God, maybe it’s the universe, but whatever it is, when songgeri plays, we feel it. Hallelujah.

+++

*Apologies: for better or worse, Aural Archipelago will always be devoted to exploring within the borders of Indonesia, even when the limits of the nation state are stretched as thin as they are in this corner of the country.

**One other musician explained that songgeri also means “thunder” in Ambai, connecting the earth-shaking vibrations of a rollicking songgeri band (especially the boom of the stembas) with thunder, which is seen as an explosive sonic display of God’s power. An alternative name for songgeri, they mentioned, is nafiri Sion, or the “trumpet of Zion,” a reference to Joel 2:1: “Blow ye the trumpet in Zion, and sound an alarm in my holy mountain: let all the inhabitants of the land tremble: for the day of the LORD cometh, for it is nigh at hand.” Pentecostalism is a particularly millenarian tradition, and some elder pastors in Kawipi explicitly said that songgeri is, just like nafiri Sion, a powerful musical signal before the end times.

***Serui people,” as people from these islands are known to outsiders, Serui being the largest town on Yapen.

****Throughout my time in Kawipi, I was told repeatedly of the last foreigner to visit Ambai, an American who had come to translate the bible to the Ambai language on the other side of the island. Folks seemed to have vivid memories of the guy, so I asked - Oh, when was that? Only to be told that it was forty years ago.

Mahikai, Terima Kasih, and Thank You to the Musicians of Kawipi:

Alexander Waroi, Dision Yowei, Siors Wanggai, Apres Waroi, Eduard Yowei, Kiki Oropa, Habel Yowei, Simson Yowei, Pileimon Waroi, Jublinus Yowei, Surasman Yowei, Herman Wanggai, Jermias Aronggear, Jusak Warembah, Yoram Rerei, Obei Aronggear, Fredi Yoko Wanggai, Yanisandoi Wanggai, Ronal Maniawas, Jekwiliam Oropa, Josep Woru, Jems Oropa, Ojo Aronggear, Oto Aronggear, Epison Yowei, Kaen Rerei, Yublinus Waromi, Yohanes Yowei, Kalep Yowei, Frans Oropa, Lodwik Rerei, Sergius Kareni, Marias Watmuri, Gerson Rerei, Feibe Oropa, Otolinda Wanggai, Herlina Woratsai, Esterlina Oropa, Debi S Oropa, Boy B Oropa, Melki Oropa